FFT-method expert validity

One product - same price? Wrong! How to protect yourself against personalised prices

If there is a lack of reliable data on the occurrence of specific events or knowledge on the consequences of decisions, there is a problem of uncertainty. Better decisions can hardly be achieved through the trained use of statistics or their transparent communication. Instead, the central question is how individual consumers can reduce uncertainty in their decision-making situation. Two scenarios are central here:

How can uncertainty be reduced (quickly, practically) for everyday problems in which consumers are left to their own devices?

How can uncertainty be reduced (quickly, practically) for everyday problems for which an expert provides advice to the consumer?

Why is it difficult to provide decision support for problems of uncertainty?

Decision problems of uncertainty are characterised by a lack of reliable data. This effectively rules out the direct selection of the best decision option. The support consists of identifying key strategies to reduce uncertainty. What do I need to ask to reduce the choice of potential information or options? What do I need to look for? What do I need to consider to sort out inappropriate options that do not meet the minimum requirements?

In contrast to consumers, experts in a particular subject area are able to identify objective shortfalls in the standard of a decision problem on the basis of fewer heuristic features. With the help of an analysis of specific consumer decision situations, possible expert heuristics are distilled into decision trees. These summarize the experts' gut feeling based on their experiences and provide consumers with a robust expertise that enables them, similar to the expert, to separate the wheat from the chaff.

This is not only important for issues where consumers are left to their own devices. Potential decision heuristics can also be combined in decision trees for consulting situations: Here it is a matter of asking the consultant the most important questions in order to be able to assess this situation robustly.

Fast-and-Frugal Trees (FFTs) are suitable decision trees that can be transparent, comprehensible to consumers and of high quality at the same time. These FFTs represent a sequence of features to be examined (Martignon et al., 2008). There is always only one branch (stop) or one arrives at the next test feature, but there are no further branches (see example below). This distinguishes the FFTs from the usual decision trees. Only the last feature in the chain has two branches.

It has been shown that FFTs enable fast and reliable decisions in various decision situations under uncertainty, e.g. in psychiatry, anaesthesiology, but also in the financial world (Aikman et al., 2014; Green & Mehr, 1997; Jenny et al., 2013). FFTs can be presented both digitally (e.g. app, website) and analogously to consumers (e.g. on posters or in brochures) in the form of a graphically illustrated, simple tree structure. This makes them an evidence-based instrument for decision support that is easy to implement. In the RisikoAtlas project it was developed and implemented for the first time for everyday consumer practice. The use of FFTs is also helpful because their application trains skills. The use of FFTs facilitates the internalisation of key characteristics for problems and stimulates critical thinking.

The order of features in an FFT is critical and must be determined in advance. There are both manual and more complex approaches using machine learning methods. Once statistically determined, this combination of features allows consumers to robustly classify decision options (e.g., whether an informed decision is possible) by independently examining those features.

How to construct a decision tree for a consumer problem - the FFT method of expert feature validity

A. What do you need?

For the evidence-based development of FFTs, all approaches (including the FFT method of expert-based feature validity) require base data consisting of three parts: Characteristics of the problem, problem cases and the respective case assessment.

Part 1 – Characteristics of the problem

First, it is necessary to clarify what the problem is and to define the concrete decision or assessment on which information should be provided. What is the decision tree supposed to deliver? Under this aspect, potential features are researched with the help of experts (e.g. workshops), colleagues, laypersons and specialist literature (trade journals, white papers, government reports and experience reports). Potential features are all those characteristics of the problem situation that could possibly be an indicator of a good or bad decision regarding the problem. It may also be worthwhile to include new features such as one's own assumptions or intuitions. A list of potential features should then have been established.

Each potential feature must be comprehensible and testable by a layperson. Ideally, the list should summarize similar features, especially if there are too many of them. It is fair to say that expert supported feature selection is the most important tool in advance, particularly when it comes to cost-effective development. After all, each additional feature requires more cases in order to allow robust development. As a rule of thumb, you can basically calculate 20 to 50 cases for each feature. Each case requires effort: Each case must be individually coded for all features and an assessment must be obtained. If you need support during this process, please consult the final report on the Risk Atlas project from July 2020 or contact us. Contact details can be found here.

Part 2 - Problem cases

Once you have made a selection of potential features, you need to find out how often and under what circumstances they occur in the real world. For this you collect material of typical decision situations, e.g. real purchase offers, videos of real consulting situations or real informational services.

If such case material of typical decision situations is not available, the FFT method of expert-based feature validity is the method of choice. Instead of the natural combinations of features in real cases, all possible virtual profiles of potential features are combined. Each combination of characteristics represents a profile and therefore a case.

Part 3 - Case assessment

For each case in your data basis, you must know or determine whether the target criterion is met or not. In the case of health information, for example, a positive assessment would be the target criterion if it enables an informed decision, otherwise it would be a negative assessment. Without this basis of already determined profiles, no model for future decision support is possible. One approach would be to test each profile or case, i.e. determine how it turned out. This involves considerable experimental effort. The alternative is the "view of the expert", which the model approach presented here was aimed at right from the start. Several independent experts evaluate each individual case (i.e. each profile, each combination of features) with regard to the objective of the development, e.g: "Does this health information allow an informed decision?

B. How do you proceed?

With the FFT method of expert-based feature validity, the significance of potential features is tested directly through expert assessments right from the start. Normalized frequency formats (... of every 100) are used to estimate the presence of each feature in relation to positive and negative target conditions. Resulting measures - positive predictive value, negative predictive value, false omission rate, false recognition rate, sensitivity, specificity, feature prevalence - are evaluated to minimize the number of target features. In addition, the frequency of occurrence of the target object is determined with experts. If you need assistance with the procedure, please consult the final report on the Risk Atlas project from July 2020 or contact us. Contact details can be found here.

This selection can be further reduced by testing laypersons on how successfully they evaluate the individual features. If you aim for six characteristics, this means that you always have to generate 2 to the power of 6 = 64 different combinations. Each feature can either be present or absent (or above or below a certain value limit). Since the experts also estimated feature prevalences, the associated probabilities can be used to estimate the profile frequency, i.e. how often certain combinations occur. This is crucial in order to weight the occurrence of the profiles in the data set realistically.

For all profiles, the expert evaluations are "collected" in a further study. Three experts receive every feature profile. This means that the expert's view can only be modeled using features familiar to them. This is qualitatively weaker than, for example, the FFT method of case-based feature validity.

The decision tree is modeled on the basis of these feature assessment profiles.

The pipeline for development can be summarized in a simplified illustration:

Modeling from tree development and cross-validation can be performed manually, but in the sense of effective modeling it is easier with the open source solution R. In addition to the FFTrees package (Phillips et al., 2017), you can also download a web solution by Evaldas Jablonskis and Uwe Czienskowski from http://www.adaptivetoolbox.net/Library/Trees/TreesHome#/. If you need assistance with this, please consult the final report on the Risk Atlas project from July 2020 or contact us. Contact details can be found here.

A Fast-and-Frugal Tree (FFT) is modeled using the portion of cases selected as training data; often 33% or 50% of cases. This FFT has a certain quality in terms of tracking down the target feature (assessment). This means it will miss cases in the real world and cause false alarms in others. To quantify this quality, either a statistical cross-validation can be performed (the determined decision tree is applied on randomly repeated cases; test data cases), or it can be applied once to a collection of cases with assessments that were put aside before modeling. Alternatively, a completely new sample of cases with feature encodings and ratings (out-of-sample) can be collected to which the decision tree is applied (additional effort).

Which quality is sufficient depends very much on the types of errors and the costs associated with the error. Finally, the model must be tested in practice with laypersons. Here a randomised controlled study is useful in which the decision intentions of consumers who are given the decision tree are compared with those who have nothing or a standard information sheet. If you need assistance with quality or evaluation, please consult the final report of the Risk Atlas project from July 2020 or contact us. Contact details can be found here.

- Aikman, D., Galesic, M., Gigerenzer, G., Kapadia, S., Katsikopoulos, K. V., Kothiyal, A., ... & Neumann, T. (2014). Taking uncertainty seriously: Simplicity versus complexity in financial regulation. Bank of England Financial Stability Paper, 28.

- Green, L., & Mehr, D. R. (1997). What alters physicians' decisions to admit to the coronary care unit?. Journal of Family Practice, 45(3), 219–226.

- Jablonskis, E., & Czienskowski, U. (2017). Decision trees online. http://www.adaptivetoolbox.net/Library/Trees/TreesHome#/

- Jenny, M. A., Pachur, T., Williams, S. L., Becker, E., & Margraf, J. (2013). Simple rules for detecting depression. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 2(3), 149–157.

- Luan, S., Schooler, L. J., & Gigerenzer, G. (2011). A signal-detection analysis of fast-and-frugal trees. Psychological Review, 118(2), 316.

- Martignon, L., Katsikopoulos, K. V., & Woike, J. K. (2008). Categorization with limited resources: A family of simple heuristics. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 52(6), 352–361.

If you would like to adopt a consumer topic from our website, you can do so in the following three ways:

- You are using a digital copy. Either you directly save an illustration or download our PDF, or you integrate the illustration via Link(a href) or iframe.

- You take your analogue copy and print out our PDF. The resolution and vector-based graphic is suitable for posters and brochures.

- You recommend the app and refer to the Risikokompass from the PlayStore and AppStore.

If you would like to develop your own model, please consult the final report on the RiskAtlas project from July 2020 or contact us. Contact details can be found here.

When using the instruments, please mention the funding agency, which is the German Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection, and the Harding Centre for Risk Literacy as the responsible developers.

Logos can be downladed here.

FFT-Methode getesteter Merkmalsvalidität

Method Natural Frequency Tree (NFT)

Method risk reading assistant for your browser

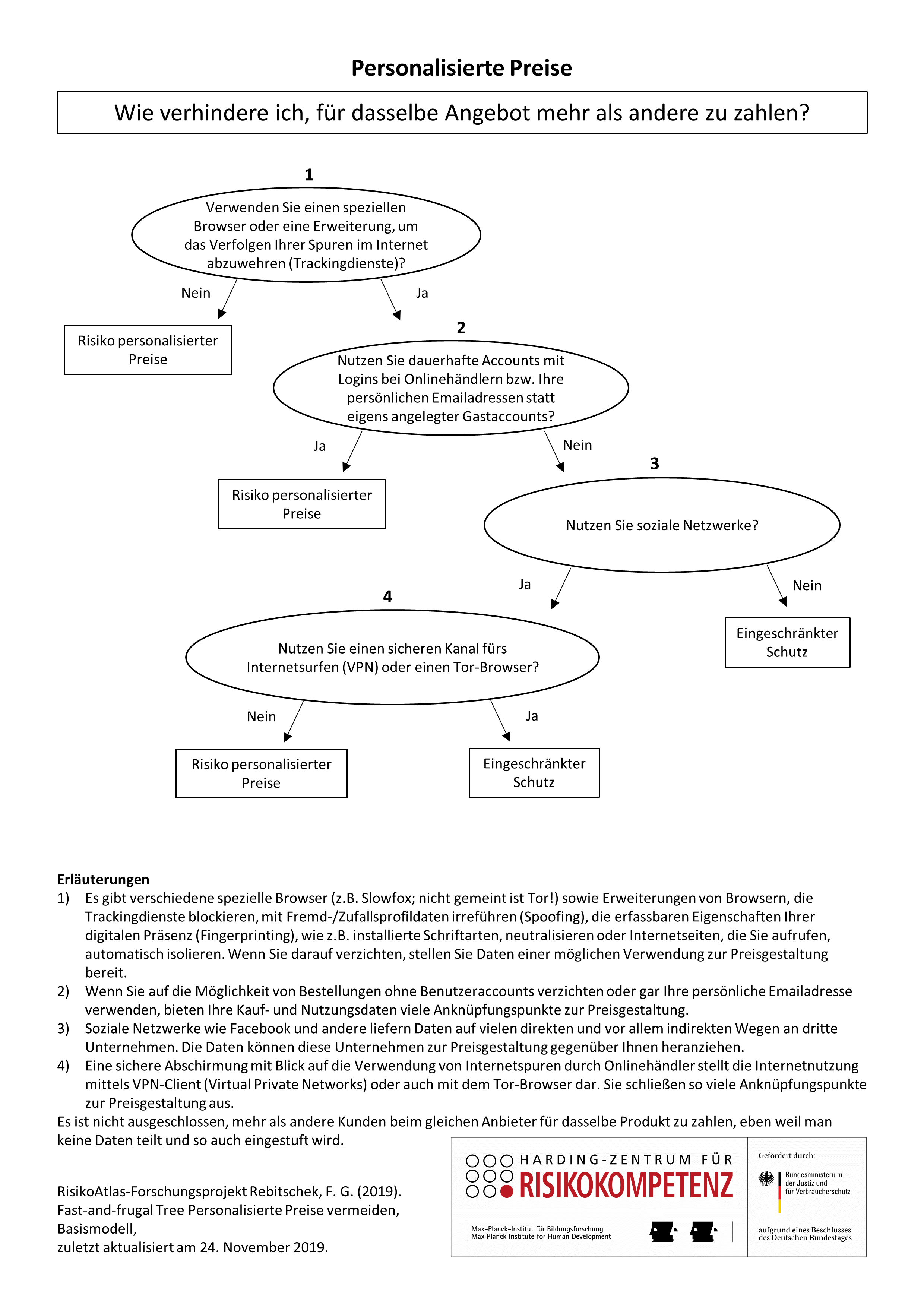

The market price of a product is usually determined by supply and demand. This price is the same for everyone - at least that is how it has been for a long time. It is also not unusual for an individual price to be negotiated between seller and buyer. For example, on flea markets, price negotiations and testing the highest price someone is willing to pay are common practice. We can assume that personalised pricing for purchases on the Internet is even less widespread, but that it is much less transparent there. If, for example, you want to buy a mobile phone via Amazon and research its price, it is quite possible that your colleague will be shown a different price for the same phone on a different terminal at the same time. Algorithms adapt the prices to your user behavior - for example, your purchase history or the number of page visits. Other personal data is also included in personalised pricing, for example, how solvent the algorithm estimates you to be.

To avoid this mechanism, it is important for you to know how you can protect yourself against personalised pricing. Our decision tree helps you to do this.

You can take further measures. Please note, however, that no data protection is ever perfect.

A further measure is:

Do not use offers which require consent for the disclosure of personal data to third parties.

Where is the data coming from?

Cases – Which served as a basis?

All 64 combinations of six critical actions (action profiles) and their evaluations served as the basis for training and test data sets.

Target assessment – How were the action profiles pre-estimated?

Each action profile was assessed by three experts.

Potential features – Which actions were considered?

Using literature studies, 32 actions were identified that could potentially contribute to or counteract protection against personalised prices.

Selection of features and modelling

Using a feature study and statistical analysis, six potential features that are assessable by laypersons were selected and given the highest validity by the experts.

The model

The FFTrees package was used for model identification (Phillips et al., 2017). The ifan algorithm was used to optimize for balanced accuracy.

What is the quality of the data?

The data set was randomly divided into training data sets (two thirds) and test data sets (one third).

The model is of the following quality:

A cross validation of the identified decision tree resulted in the following quality measure: balanced accuracy = 0.81; correct classification of protective measures from profiles (share of 14% in the test set) with 0.67. This means that in 67 out of every 100 cases protective measures contribute to an action profile for which experts attest limited privacy protection against personalised prices.

The correct classification of vulnerable actions occurs in 95 out of every 100 cases that experts recognised as such. The decision tree shows very clearly what the weak points are.

Potential for development

Continuous further development of the underlying training data due to changes in the market situation.

Empirical evaluation with consumers

All research results on the fundamentals and on the effectiveness of the RiskoAtlas tools in terms of competence enhancement, information search and risk communication will be published together with the project research report on 30 June 2020. If you are interested beforehand, please contact us directly (Felix Rebitschek, rebitschek@mpib-berlin.mpg.de).

Sources

• Phillips, N. D., Neth, H., Woike, J. K., & Gaissmaier, W. (2017). FFTrees: A toolbox to create, visualize, and evaluate fast-and-frugal decision trees. Judgment and Decision making, 12(4), 344-368.

Last update: 26 November 2019.